I’ve previously shared methods for making ‘cheat’ homemade milk chocolate, dark chocolate, and white chocolate. However, these methods require combining store-bought cacao/cocoa powder and butter. Having done so, I wanted to learn how to make chocolate from the cocoa beans to a bar! Following a 7-step process of harvesting, fermenting (and drying), roasting, grinding, blending, tempering, and molding – you can make delicious homemade chocolate from cocoa beans. Best of all, this method is super easy to tweak. Whether you want milk vs. dark chocolate and what percentage chocolate to sugar- no problem! This is going to be a long one so let’s get straight to it!

How To Make Chocolate From Scratch

Step 1: Growing and harvesting

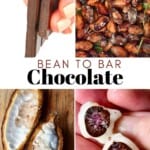

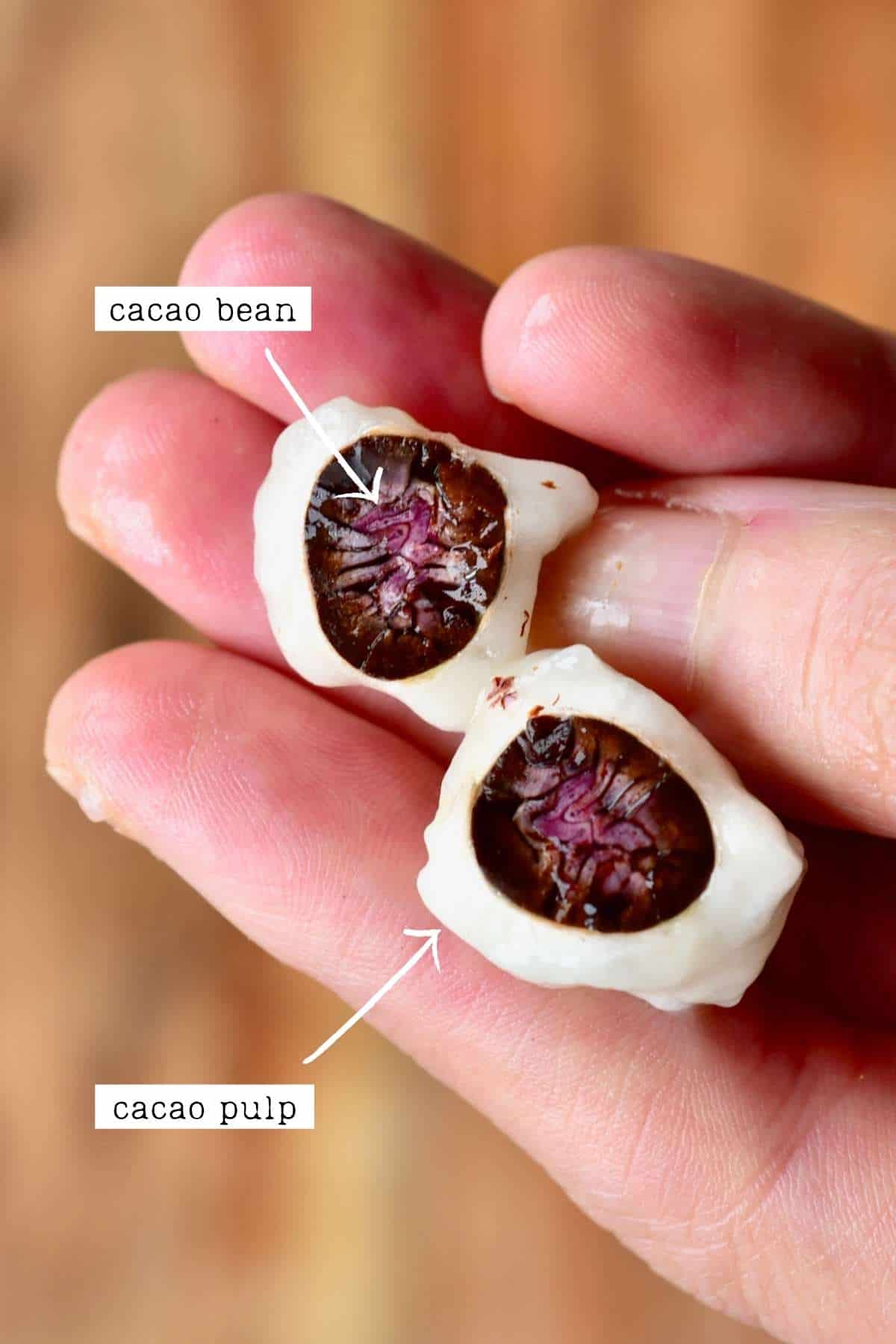

These two steps are the only ones that I have no part in, but I thought I’d include them in the process for full transparency. The cacao tree (also called Theobroma Cacao) is grown in tropical climates across the globe. These trees produce a fruit which is the cacao pod that grows on the branches and trunk of the tree. Interestingly, the pods don’t all ripen simultaneously. They also grow in different colors and shapes depending on the variety of the plant. So it takes a certain level of expertise in harvesting the pods at the correct time. To harvest the pods, a machete is used to remove them from the tree without damaging the tree’s flowers. This ensures more pods can continue to grow. To begin the process of making chocolate the first step is to open the cacao pod. When doing this at home I find it easiest to hit the shell with something like a wooden muddler or hammer, if you have one. If you want to save the pod to be repurposed into cups/bowls then it may be easiest to carefully cut the shell with a hand saw so it has an even slice that can be further refined/sanded. For more information on how to dry and seal the pod to become safe for food usage, you can see the method I used for these coconut bowls. Once you cut open the cacao pods, you’ll see the cacao beans, which are covered in a viscous white ‘mucilage’ coating. Definitely not what we think about when thinking about chocolate. The white jelly pulp/coating is actually edible too. Traditionally its eaten as-is or blended with water into a juice ‘cacao juice’. The flavor is sweet-tart/acidic and has similarities with soursop. The hard bean inside is the cacao bean. At this point we have yet to ferment or roast is so it’s fairly ‘wet’ looking with a purple color and brain like appearance when you cut into it due to all the individual nibs inside. It’s not recommended to eat the raw cacao beans as they will be very bitter and unpleasant – instead, we need to process them first.

Step 2: Fermenting the cacao beans

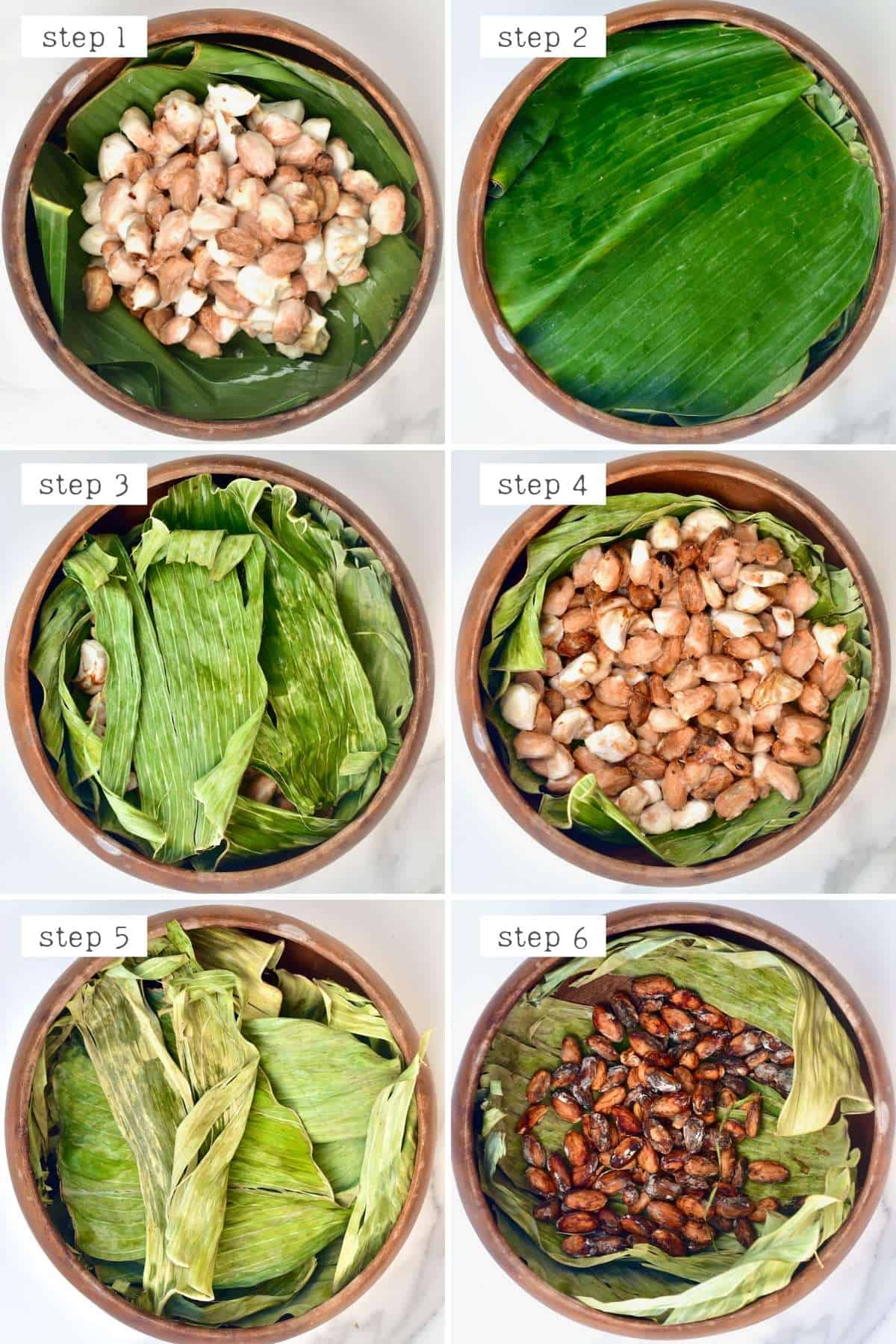

Once the beans are exposed to oxygen, the fermentation process can begin – done in a very similar way to making tempeh. Traditionally, the beans are contained within banana leaves or perforated wooden boxes (for airflow) topped with banana leaves, mixed and turned occasionally. As they ferment, the temperature of the beans will naturally rise to between 104-122ºF/40-50ºC, thus encouraging the fermentation process. Following this step, the beans are then further dried – often in the sunlight. However, I use a dehydrator for this step which ferments and dries them at the same time. This stage can take up to eight days to fully complete (depending on the type of bean used) and is critical in developing the cacao flavor and reducing the astringency. Chocolate made with unfermented beans won’t have the same richness or ‘body’ to it. When doing the process at home there are two methods; the first is a way that mimicks the traiditonal version, and the second uses a dehydrator.

Method 1: With banana leaves

I lined a large bowl with banana leaves then filled it with the beans, topping it with a layer of banana leaves. Just like when allowing bread to rise, this now needs to be placed somewhere warm. Between 40-50ºC is the optimal temperature. This can be helped by placing them next to a heat source or even placing a hot water bottle within the container you use (that can be removed and replaced 1-2 times a day if needed). As the beans heat, they will start to produce their own heat too (usually after a couple of days), which helps the process along. As the beans ferment the white layer will break down into a juice so it’s a good idea to drain this once per day (or twice if possible) and mix the beans.

Check the beans a few times during the process in case there are any that look moldy – remove these and continue with the process. This process takes around 5 days but can take slightly longer depending on the heat, humidity, and individual beans. I allowed my beans to ferment and dry all while wrapped in the banana leaves – some methods may change the process for drying but I find it unnecessary.

Method 2: With a dehydrator

Place the beans in a single layer across the dehydrator trays, leaving space between the beans for airflow. Run the dehydrator at 104ºF/40ºC for several days. This can take between 5-10 days; I did it for 5 days.

During this process, the beans will turn from a purple color to a pink/reddish-brown to a darker brown and will massively reduce the liquid content of the beans. It doesn’t work quite as well as the traditional method but will work.

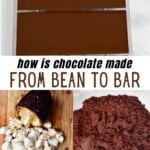

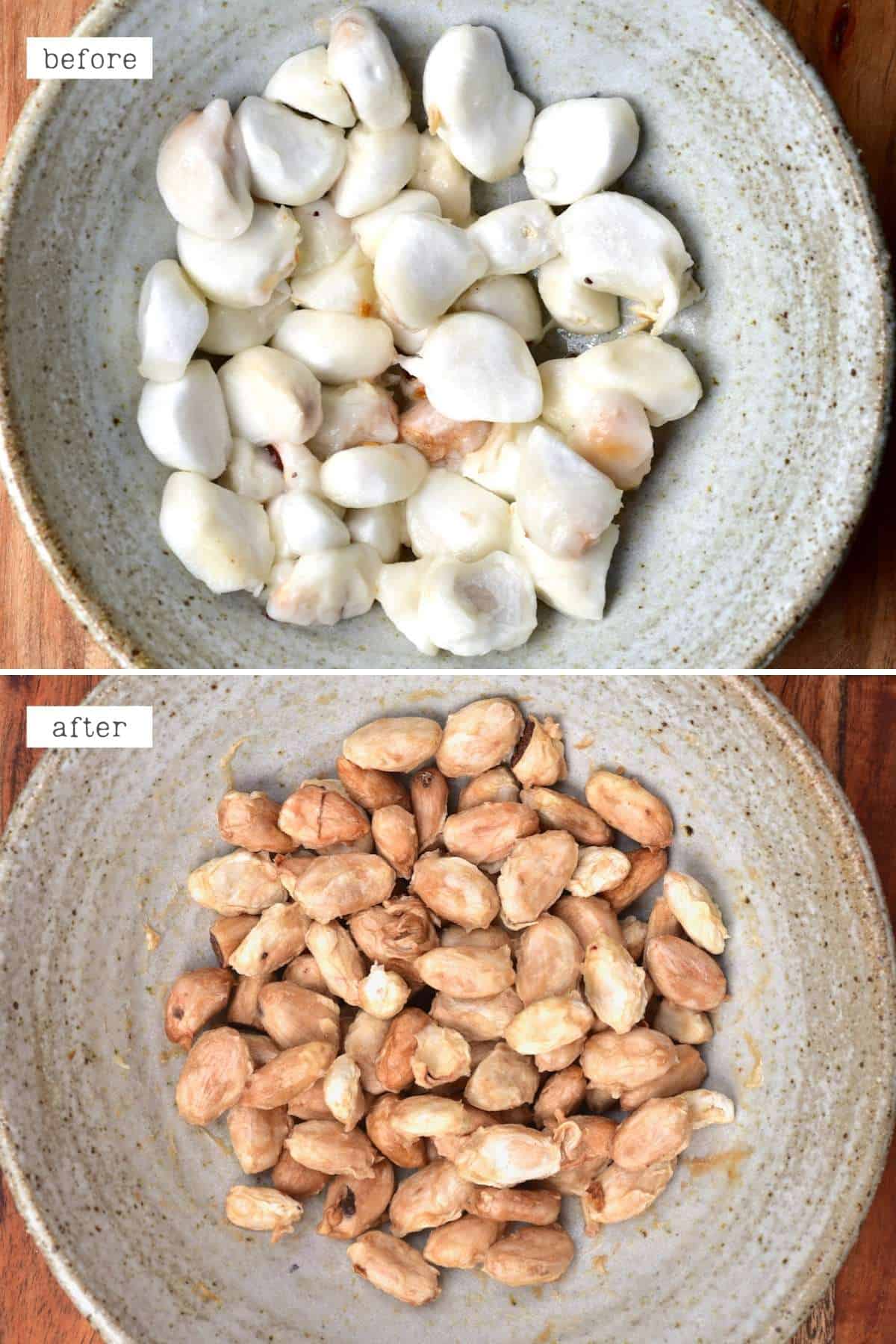

Step 3: Roasting the beans

Roasting the beans is important to get rid of any remaining liquid content from the beans. However, it also develops flavor and kills any bacteria on the beans. Most importantly, it helps separate the outer husk (shell) from the inner bean (cacao nibs). No matter how this is done, it tends to follow a similar technique: heating the beans at high temperature (which will help separate the husk and nibs within) then slowly reducing the temperature (to continue the roasting without burning the beans) until they begin to ‘pop,’ without burning. However, at home you can really experiment with this and changing temps.

Before roasting the beans, you’ll first need to remove any beans that are broken and/or smell moldy, etc.Then, lay the beans in a single layer on parchment-lined oven tray/s. You can roast the beans whole then peel them or peel them first before roasting.

If you peel the husk first then you can break the bean into the nibs and have more surface area while roasting. That way they roast faster and more evenly. However, it is much easier to peel them after roasting so the preference is up to you.

Roast the beans in the oven at 120ºC/250ºF fan-assisted for between 15-20 minutes for a fairly light roast.

The way you roast the beans will have a big impact on flavor and you can choose to do a light, medium, or dark roast. This is something I’m still experimenting with and will update over time. During the end of the roasting step (if roasting as whole beans), air pockets will escape the beans, making popping sounds – this is normal. When they’re almost done, you may also smell a ‘brownie’ smell. The husk should also come off the beans easily.

Step 4: Cracking & Winnowing

The title makes this process sound complicated; however, what cracking and winnowing of chocolate actually means is just removing the cocoa bean from the shell to reveal the cacao nibs inside. If you’ve done this before roasting then – skip this step! While commercial chocolate will do this process with machines, it can be done by hand.

There are several ways to do this, but pressing the beans between your fingers should be enough to loosen the shell. Do this with all of the beans putting the shells in a separate bowl from the beans (nibs). Next, break the beans down into individual nibs. You can do this by hand or place all the beans into a bag and bash with a rolling pin.

These cacao nibs can now be eaten as is or further processed into chocolate. Interestingly these nibs are made up of around 50% cacao solids (what will become cocoa powder) and 50% cacao butter.

Step 5: Grinding and Conching

If you grind the beans as they are now then you will end up with something that looks similar to cocoa powder. Except that it has a higher fat content as the beans haven’t been processed to separate the cacao butter from the solids. However, when making chocolate at home you can create the chocolate without separating the two. You can add extra cacao powder or butter to further tweak exact ratios if preferred. What you do need is a piece of equipment called a chocolate melangeur (melanger), i.e., a stone grinder. This is used to grind the cocoa bean nibs to a paste called chocolate liquor before undergoing a process called ‘conching.’ There’s no alcohol involved, it’s called this due to its liquid form. This step removes certain unwanted ‘volatiles’ within the mixture as it heats and leads to evaporations and distillation of these elements – like acetic acid, for example. It also helps to coat the cocoa solids with fat to reduce the viscosity of the molten chocolate. This process is also important for developing flavor within our chocolate. Higher-quality chocolate often has a higher conching time – for a richer, milder taste. This is also the stage where (in commercial operations) the chocolate liquor could be separated into cacao butter and solids. To do this, a hydraulic press would be needed to separate the cacao mass into the butter and powder (like we can buy from stores). If you’re wanting to make chocolate from cacao/cocoa powder and cocoa butter then you can follow a method like I used for this dark chocolate.

Using A Chocolate Grinder

Even if you’re using a grinder, it’s still a good idea to pre-grind the nibs into smaller pieces.

You can do this in a high-speed blender, food processor, or electric coffee/spice grinder. If using a small grinder, then do this in batches. Then add the ground nibs to the chocolate grinder (melangeur) and allow it to run for about 12 hours.

The Manual Method

Like above, it’s best to use a high-speed blender, food processor, or electric coffee/spice grinder to start this process. However, the best results are with the small grinder.

With a grinder: Add the nibs in small portions to the grinder and grind into a paste. The cacao butter will start to extract from the nibs (similar to when making nut butter), and the powder will become wetter and more paste-like.

This process can take several minutes, so I suggest allowing the machine a break after every minute or so.

With a high-speed blender: first, blend the beans into a powder until the point they are just starting to look slightly wet. Then, transfer them to the microwave for 20-30 seconds (depending on how powerful your microwave is). This will help to encourage the extraction of the cacao butter. Finally, add the nibs back to the blender and process into a paste.

At this point, no matter which method you used, you can add the powdered sugar (never liquid!) to your grinder/blender (you can use granulated if using a mortar & pestle, but it will help to use powdered sugar for best texture) and continue to process slightly more. Next, it’s time for the ‘conching’ step.

Heat a mortar and pestle in the oven for just a few minutes (until warm but not too hot to touch). Then add the cocoa liquor and use the mortar and pestle to manually grind this until you can no more. This will never get as smooth as it will with a chocolate grinder, but every little bit helps and will change the flavor and texture.

When doing it this way, you need to add additional cacao butter as it will never get as smooth as it will with the wet grinder/conching method. So the extra butter will help with consistency – for a smoother, creamier, glossier texture. Don’t add more than 10% of the total chocolate weight, though (i.e., 10g per 100g bar chocolate)

Taste the chocolate every 5-10 minutes. When you are happy with the flavor, the chocolate is ready for the next step.

Note: If you’ve made a large batch of chocolate (around 1 lb/500g), you can conch it using a stand mixer with the paddle attachment. Whip it on low speed for around an hour. Chef’s note: To obtain raw cacao powder with the fat inside, you just need to grind the nibs. Sieve a few times so the powder is fine.

Step 6: Temper the chocolate

Tempering chocolate is the process of strategically raising and lowering the temperature of the chocolate to form a specific crystal structure. Once temepered, this yields shiny, glossy, snappable chocolate that holds its’ shape at room temperature. You don’t have to do this process at all if preferred. You can also mold the chocolate for now to temper at a different time. There are three main methods for tempering chocolate, which I discuss in a separate post.

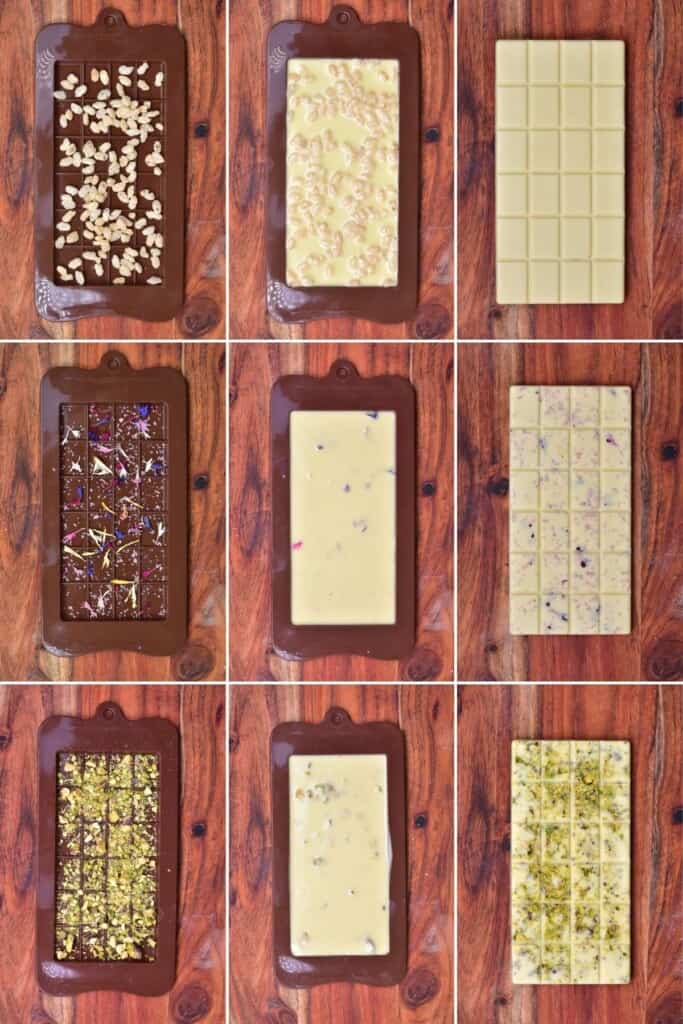

Step 7: Molding the chocolate

Finally, it’s time to pour the chocolate into your mold of choice to set it into the final chocolate product.

Pour the prepared chocolate into your mold of choice, tapping it against your kitchen counter to remove any air bubbles and help it settle. Allow the chocolate to set fully (best done at room temperature) before de-molding and wrapping. I find that polycarbonate chocolate molds work best, even better than silicone molds. To prep polycarbonate molds it’s best to use cotton balls and a type of fat-soluble sanitizer. Water can leave marks and a sponge can create micro scratches that will affect the shine.

How To Store Chocolate

The rules for storing chocolate will change somewhat depending on whether or not you’ve tempered it. Untempered chocolate is best kept in the fridge or freezer, wrapped tightly. It’s important to note that chocolate absorbs other flavors and aromas, so it’s important to either wrap it carefully or store it within an airtight container (no one wants chocolate with a garlic-y aftertaste!) For tempered chocolate, it’s actually best to avoid refrigerating the chocolate. This is because temperature fluctuations can cause the chocolate to bloom (where it has white sugar crystals on the chocolate giving it a moldy/dusty appearance) and will affect the taste and texture. Instead, store the chocolate in a cool, dry place away from sunlight. Either way, the chocolate will last for months this way!

Recipe Notes

To speed up the process, you can purchase raw cacao beans, usually from local bean-to-bar chocolate makers (for smaller quantities). It’s best to buy raw beans and roasting them yourself. It can be hard to remove the beans’ shell in pre-roasted ones. To speed it up even further, you could use cocoa nibs. If they’re raw, you’ll still need to roast them; if not, then you can get straight to grinding. Depending on where you source the cocoa beans from, the flavor can vary massively, so it’s worth experimenting with. When using a mortar and pestle to grind the beans, it’s impossible to achieve the same smooth mouthfeel as machine-ground chocolate. So, you’ll be able to detect some slight texture in the bar.The particles within chocolate are measured in microns (1 micron = 1 millionth of a meter). Our tongues can feel the grain of anything about 25 microns; thus, most chocolate aims to be between 15-25. Cacao nibs are made up of around 50% cacao butter and 50% powder – which is why many homemade chocolate recipes (like my own dark and milk chocolate methods) combine prepared powder and cacao butter for a super-quick chocolate process.Don’t use liquid sugar or add-ins: These can cause the chocolate to seize. Instead, use powdered sugars and candy/chocolate-specific flavorings when flavoring the chocolate bar.

Related Recipes

How To Make Milk ChocolateHow To Make Healthy Dark Chocolate3 Methods to temper chocolateHomemade powdered sugarHow To Make White ChocolateHomemade Filled Chocolates (Vegan Chocolate Candy)

If you try this bean-to-bar chocolate process , I’d love to hear your thoughts/questions below. Also, I’d really appreciate a recipe card rating below, and feel free to tag me in your recipe recreations on Instagram @Alphafoodie! Please note that all information included within this post has come from lots of research and personal experience. I am not a professional chocolatier and not an ‘expect’ in chocolate making.